One winter, when work was scarce, one Panther Valley coal mine worked full-time for what felt like weeks on end. Rather than celebrate their good fortune, they went on strike. See, miners in the next town over had not worked in weeks, and the strike was to force the coal company to bring their neighbors back to work. Even if it dropped their own earnings to poverty levels. The strike continued until men in the local coal mines all shared an equal amount of work time. This was the equalization movement.

The bosses didn’t like it. The union didn’t like it. But the miners enforced it from below to keep their entire valley afloat through the lean years of the Great Depression.

As the mines closed in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, the demand to share working time arose from rank-and-file miners across Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Coal Region. United Mine Workers president John L. Lewis opposed it, often times violently. The push for equalization led to the expulsion of large numbers of Wilkes-Barre area miners, who then formed their own union for employed and unemployed alike. Bitter street battles erupted between factions, scores of people were murdered, and the leader of the rival (“rump”) union was assassinated in his home on Good Friday.

In the southern region, workers pushed for equalization inside the UMW by day and took matters into their own hands at night—with bootleg coal. Union locals launched various equalization strikes but were never able to build the solidarity between employed and unemployed to do so effectively. Eventually so few miners were employed that equalization became impossible anyway. Zero divided by anything is still zero.

The Panther Valley is where the equalization movement triumphed. They went around the union, forming the Panther Valley Equalization Committee (PVEC) with support and leadership from local clergy and businessmen. Unlike the UMW, this community-labor organization had no contract with the coal company to violate. The UMW turned a blind eye to the relatively small valley, given the strife they had already created in their most crowded district.

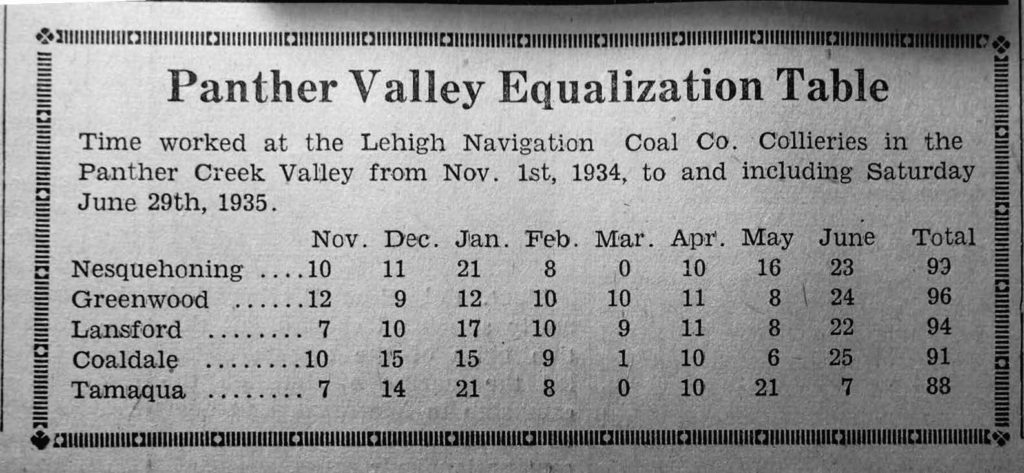

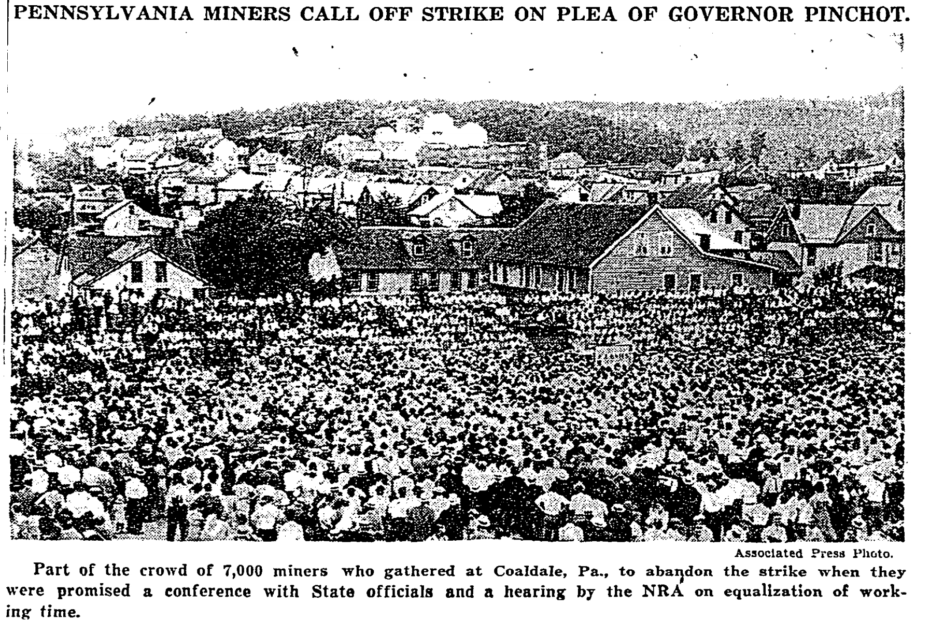

Across 5 towns, over 10,000 people marched and struck to initiate the plan, forcing it on the coal companies. Smaller enforcement strikes periodically balanced work-time between mines when the company refused. The local newspaper ran a time-table so everyone could keep track.

“The well-being and welfare of human beings is far more important than profit, and should be given the right of way in the present emergency. The so-called ‘high’ cost or lesser efficient collieries must be allowed to stay in business if the purpose of the NRA to get people back to work and to increase the purchasing power of the people is to be accomplished…

“…is not the employment of the big army of idle mine-workers of vastly greater importance to the nation than profit for the few?”

-Rev. John Pounder, First Baptist Church, Lansford, PA.

Unlike the bootleggers, PVEC had political goals. They dominated the local body of FDR’s National Recovery Administration and put pressure on the national NRA to incorporate equalization into the coal code. They pushed for a 5-day, 30-hour workweek, and for the government to buy coal and distribute it as relief to the poor. PVEC’s president, newspaperman James Gildea, was elected to US congress, where he was a friend of the bootleggers as well (although never without a little conflict).

Equalization did not leave people well-off, but it carried their communities through the Depression united and without destitution. The UMW grew soft to it later in the decade. As with so much else, World War II ended the movement as industry boomed and the draft sucked up young labor. After the war, when the industry began its second collapse, miners launched a new equalization fight which ended in sorrow rather than solidarity. Because of this, equalization became a bitter idea that was soon forgotten by the following generations.

Read more about the equalization movement and the involvement of the bootleggers in The Bootleg Coal Rebellion: The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry: 1925-1942 by Mitch Troutman. For the most complete telling of the Panther Valley story, see chapter 3 in The Face of Decline: The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region in the Twentieth Century by Thomas Dublin and Walter Licht. Similar but unrelated(!) equalization battles took place at the same time in Barberton, OH and Woonsocket, RI. For more on that see We Are All Leaders: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930s by Staughton Lynd.

this is a great piece..thanks for the history !

Comments are closed.